To Complain or Not to Complain. That is the question.

Workers in the Age of Social Media

In the age of Twitter and social media postings, we have many opportunities to complain and air our grievances. Far be it from me to preach restraint or raise the ire of free speech advocates. However, as we tell our kids, with freedom comes responsibility. More precisely in the employment law arena, excessive or petty complaints can be as damaging to your case as no complaint at all.

The Importance of Making a Complaint

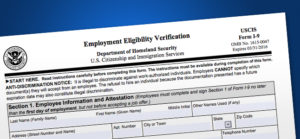

First, I want to make it clear that workers have not only the right, but in my opinion, the moral duty to oppose discriminatory, harassing, unlawful and abusive behavior in the workplace. Not only the the behavior that you have experienced, but also the discrimination you have seen others endure. As both a former prosecutor, as well as an employment attorney, I have seen good cases stalled or derailed because witnesses “don’t want to get involved.” This allows misconduct to go unpunished and in many circumstances allowed to continue and grow. Making complaints also benefit employers — as it puts them on notice of potential problems, allowing them to investigate and take proper disciplinary action. In some legal claims, such as sexual harassment, an employer may not liable unless they first had prior notice of sexual harassment, and then failed to take prompt remedial measures.

Ok, now that I have told about you how important it is to make a complaint, let’s talk about the damage that excessive or petty complaints can have on even the best cases.

Pick Your Battles Carefully

Like most employment attorneys, I have had cases with solid evidence of discrimination or retaliation, but excessive complaints unrelated to the unlawful conduct watered down the appeal of the case to a point that the settlement value was a fraction of what it should have been worth. Here are two examples. In one case, “Fred” had a very solid race discrimination case with evidence of racist comments and disparate (unfair and different) treatment compared to non-black employees. Fred, however, was a member of a union whose culture it was to complain and file grievance for every minor issue. At trial, the defense attorney cross examined Fred about a multitude of petty grievances over the years (he probably had at least 50), and portrayed him as a serial complainer. In the eyes of the jury, the complaint of discrimination was covered in an avalanche of petty gripes.

In a second case, “Maria” was the only Hispanic in a professional position with her company, and she was demoted to a lower level position not commensurate with her degree or experience. Upset with the demotion, Maria began making a barrage of written complaints that bordered on the bizarre, including one in which she accused her supervisor of “mad dogging” her. Eighty percent of Maria’s deposition by the defense lawyer was not about the legal claim, but rather the multitude of petty complaints in which she had to admit she had no evidence to support them other than her perception. In both examples, the sheer number and/or the pettiness of the complaints eroded the credibility of the plaintiffs and created a distraction from the employer’s discriminatory conduct.

Your Complaint Should Serve as a Light Not a Shadow

My friends, employee complaints are essential to proving many legal claims. These complaints, however, should be concise, professionally worded and focused on the unlawful conduct. An employment attorney can often assist in this process. In the end, making a complaint should serve as a light that illuminates an employer’s wrongdoing, not a shadow that darkens your credibility.